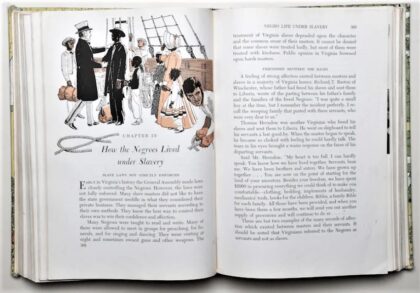

This was the education diet that Virginia’s leaders fed me in 1967, when my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Stall, issued me the first book in the series deep into the second decade of the civil rights movement. Today, Virginia’s symbols of the Lost Cause are falling. But banishing icons is the easy part. Statues aren’t history; they’re symbols. Removing a symbol requires only a shift in political power. A belief ingrained as “history” is harder to dislodge.

The lead historian for the seventh-grade edition was Francis Simkins, of Longwood College in Farmville. His 1947 book, “The South Old and New,” was an articulation of the Lost Cause. Slavery was “an educational process which transformed the black man from a primitive to a civilized person endowed with conceits, customs, industrial skills, Christian beliefs, and ideals, of the Anglo-Saxon of North America,” he wrote in that book. During the Civil War, enslaved people “remained so loyal to their masters [and] supported the war unanimously.” During Reconstruction, “blacks were aroused to political consciousness not of their own accord but by outside forces.” Spotswood Hunnicutt, a co-author, believed that as a result of post-bellum interpretations, students were “confused” that “slavery caused a war in 1861.” The commission was “looking after the best interest of the students.” The “primary function of history,” she concluded, was “to build patriotism.”

In the fall of 1967, I suppose I digested what I was fed. But later in the school year, I would absorb events that defined an era: the Tet Offensive and the erosion of our acceptance of the government’s assertions; the assassinations of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy; the riots outside the Democratic National Convention. By the time fifth grade started, I was reading this newspaper and questioning everything. My particular curiosity propelled me beyond my textbook. But only while watching city workers take down Stonewall Jackson’s statue in Richmond did I wonder how that series of books came to be.

Here’s what Simkins and Hunnicutt (and their colleagues) left out: the revolution that had begun in 1951 in their hometown. In Farmville, Black high school students went on strike over unequal facilities and then sued. The students, led by Barbara Johns, lost in trial court, but Dorothy E. Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County became one of the five cases consolidated in the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education.

Mrs. Stall, bless her heart, didn’t mention that Virginia students — perhaps some of my classmates’ siblings — didn’t go to school for several years as state leaders executed “Massive Resistance” in response to Brown’s directive to integrate schools. We weren’t taught that most of the state’s newspapers participated in an allied effort coordinated by the editor of the Richmond News Leader, James J. Kilpatrick, who went on to a respectable career as a columnist and a slot on “60 Minutes” opposite Shana Alexander.

No one told us that state Attorney General J. Lindsey Almond Jr., who described himself as “the most massive of all resisters,” Dean writes, was invited to edit the seventh-grade text. Or that (White) voters elected Almond governor with 63 percent of the vote in 1957, the year the textbooks first appeared in classrooms.

Massive Resistance collapsed in 1959, when federal and state courts ruled, on the same day, that closing public schools was unconstitutional. Arlington schools, where I started kindergarten in 1963, quickly admitted Black students (I, a White kid, remember none in mine, after attending a predominantly Black preschool), but other districts slow-walked integration long after the Supreme Court ruled against Prince Edward County again in 1964.

Is this why President Richard Nixon asked Powell to join the Supreme Court in 1969? Powell had not yet written the confidential memo for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce calling for a coordinated campaign to defend American capitalism. He was only a name partner in the law firm that had defended Prince Edward County, the champion of “citizenship education” and, he told Nixon, an inadequate choice.

Powell joined the court in 1972. Days after he was sworn in, the education board voted unanimously to withdraw the books. Yet they remained: Pat Lang, a McLean mother, protested my fourth-grade book in a letter to The Washington Post in October 1977 — the fall I started at the University of Virginia and two decades after its initial dissemination. “Roll over, Kunta Kinte,” Lang wrote, appalled, and went on to quote some of the lies her fourth-grade daughter was being taught.

Two days after Richmond dismantled Stonewall Jackson’s statue, President Trump went to Mount Rushmore and claimed, in language recalling Powell’s: “Our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values and indoctrinate our children.”

Well, yes, that’s what political leaders have done for generations. Just read my Virginia history textbook.

Bennett Minton was a member of the Unitarian Universal Church of Arlington from 2001 to 2018, when he moved from his domicile of nearly six decades to Portland, Oregon. As he was at UUCA, he remains involved in politics as an organizer and lobbyist, paid by no one. He writes on politics and history on his blog, TransformationalCitizenship.com, from which this article was adapted.